An Inside Look of Analogue to Digital & Digital to Analogue Audio Conversion

A microphone captures an analogue sound wave, transmitting it as electrical signals to an Analogue-to-Digital Converter (ADC). The ADC transforms these signals into digital values, allowing storage on a computer.

When playing digital audio, the process reverses: Digital values are converted back into Analogue electrical signals using a DAC (Digital-to-Analogue Converter). These signals drive a speaker, causing the speaker cone to vibrate, generating sound waves and Analogue noise in the air.

Analogue to Digital Converter – Converts Analogue sound into digital signals that can be stored on a computer

Digital to Analogue Converter – Converts digital signals stored on a computer into Analogue sound that can be played through devices such as speakers

The ADC process primarily involves two stages: Sampling and Quantization

Sampling & Quantization or Digitization of Audio signals

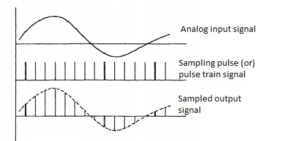

The conversion process starts with Analogue to digital conversion. The process of ADC must accomplish two tasks i.e., sampling and quantization. Sampling stands for the number of samples (amplitude values) captured at regular time intervals. The sampling rate is number of samples taken per second which is measured in Hertz (Hz). If we record 48000 samples per second, the sampling rate would be 48000 Hz or 48 kHz.

Sampling rate (Fs)= 48 kHz

Sampling period (Ts)= 1/Fs

Sampling rate Vs Audio frequency

A smaller sampling interval permits a higher rate, correlating with increased audio frequency and better sound quality, albeit larger file sizes. To ensure lossless digitization, the sampling rate must be sufficiently high. The Nyquist theorem states that digital samples can’t accurately represent frequencies above half the sampling rate. For perfect reconstruction, the sampling rate needs to exceed double the highest audio frequency, often expressed as Fs > 2 Fmax, as per the Nyquist frequency.

Conceptual diagram illustrating the sampling process of a sound wave

Aliasing emerges as an artifact when a signal is sampled at a rate lower than twice its highest audio frequency, leading to discrepancies between reconstructed samples and the original continuous signal. This phenomenon is determined by the frequency and sampling rate of the signal. For example, using a 38 kHz sampling rate introduces aliasing for frequency components surpassing 19 kHz.

Anti-aliasing Filter is process of aliasing can be avoided by using low-pass filters or anti-aliasing filters. These filters are applied to the input signals before sampling to restrict the bandwidth of the signal. Anti-aliasing filters remove the components above Nyquist frequency and allow to reconstruct the signals from digital samples without any additional distortion.

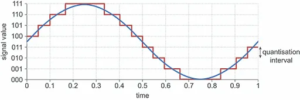

Bit-depth represents the quantity of bits allocated per sample. Computers process and store information solely in binary digits, denoted as 1 or 0. A greater number of bits signify increased information stored. Therefore, higher bit-depth translates to capturing more data for precise outcomes.

Quantization of Audio Signals

Audio signal quantization refers to converting infinite Analogue values into finite digital values during Analogue-to-digital conversion (ADC). Bit-depth significantly influences the precision and quality of these quantized values. For instance, with a 16-bit audio signal, 2^16 (65,536) values represent the maximum amplitude range.

This means the signal’s amplitude is divided into 65,536 samples, each assigned a discrete value from a set of possible values. Though this process may result in a slight perceivable loss in audio quality, it’s typically imperceptible to human ears. This loss, termed quantization error, stems from disparities between the input and quantized values.

Diagram illustrating the quantization process on a waveform

Mono, Stereo and Surround Sound in Digital Audio

Mono, short for monophonic, consolidates all sounds into a single channel, utilizing only one channel during signal conversion to sound. Despite multiple speakers emitting sound, mono creates the effect of a singular source emanating from a single speaker.

Stereo, or stereophonic, stands in contrast to mono sound by employing two distinct channels, left and right. This setup creates the impression of sounds emanating from various directions, contingent upon the speaker to which the signal is directed. Offering a multidimensional auditory experience, stereo ensures uniform coverage across both left and right channels.

The shift from mono to stereo has occurred due to superior audio quality and the inclusion of multiple channels.

Surround sound heightens the fidelity of audio playback by employing numerous channels, creating a sensation of sound originating from three or more directions. Beyond the standard left, right, and centre, it encompasses front and rear sources, enveloping listeners with sound from all directions. This technology finds extensive application in audio systems such as home theatres.

Conclusion: The journey from analog to digital and back again is a fascinating exploration of technology’s impact on sound. By understanding the intricacies of audio conversion, we gain insight into how we can create, manipulate, and enjoy sound in the digital age. By exploring the nuances of analog to digital and digital to analog audio conversion, we gain a deeper understanding of the technology shaping our auditory world.